Review: The Union League’s Revisionist History

A City Divided: The Civil War, Philadelphia & The Union League

At the Union League Heritage Center, 140 S. Broad Street (ring doorbell for access through street level door at front of building; accessible entrance reportedly available through side door on Sansom Street). The exhibit runs through December 2024. Admission is free.

Public hours: Tuesday and Thursday, 3:00-6:00 PM; second Saturday of every month, 1:00-4:00 PM.

The Union League’s museum exhibition, “A City Divided: The Civil War, Philadelphia & The Union League,” should be of interest not just to Civil War history buffs, but to anyone curious about Philadelphia’s political, racial, and cultural history—past and not so past. And not just for what it reveals about the Civil War period, but how it reflects on the Union League today.

From Honoring Lincoln to Honoring DeSantis

By way of background, the Union League, founded in 1862 to support the Union during the Civil War, has been in the news for the controversy about its presentation of the League’s gold medal of honor early last year—the same award given to President Lincoln in 1863—to Florida Governor (and now Republican presidential candidate) Ron DeSantis.

Outside the League’s award ceremony, members of the local NAACP and others joined in a large street protest, and the League received a thorough drubbing in news media opinion pieces.

With this background in mind—a city divided, indeed—I stepped through the street-level door at the front of the League clubhouse on Broad Street.

And as always when thinking about this conservative Republican organization, I experienced a moment of almost dizzying cognitive dissonance—how did the Republican Party of the Civil War Union League—yes, the party of Lincoln—become the party of Donald Trump?

According to Vox, this can be answered in 13 maps or 7 minutes.

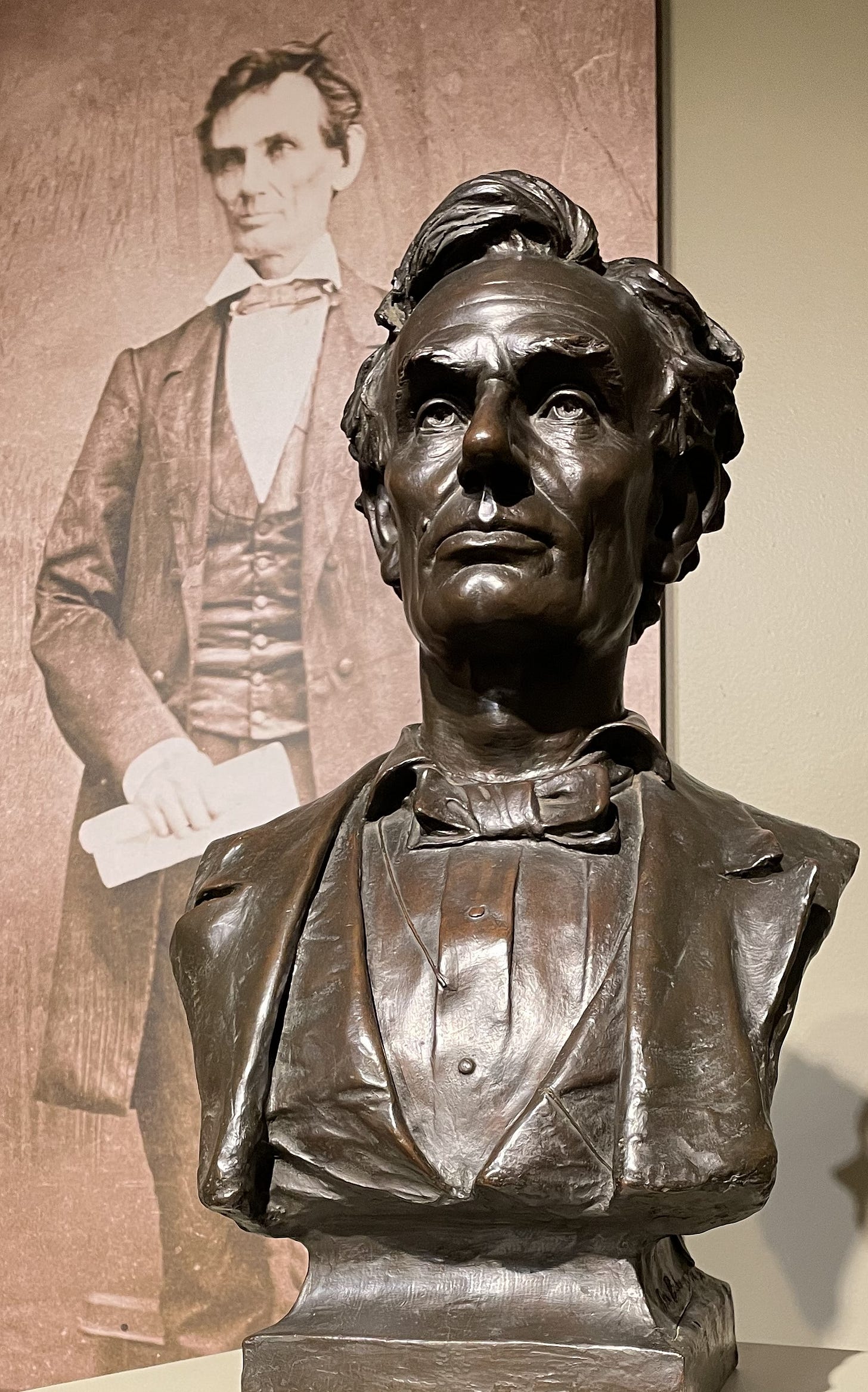

Inside, “A City Divided” is presented in only one large room, but it is a full and information-packed display, heavy on written narratives that accompany period sepia-toned maps and images enlarged floor to ceiling. A detailed Civil War timeline organizes the exhibit, and included are a smattering of period documents, objects, and art works (not one, but two Lincoln busts), and, perhaps surprisingly, only a few weapons.

Confronting Common Myths

At the outset, the exhibit attacks some common myths. Foremost is that Philadelphia, as a “northern city,” was uniformly on the side of Lincoln, supporting the war to end slavery and establishing full citizenship for the formerly enslaved. On the contrary, the exhibit explains, Philadelphia was the “most southern of Northern cities,” and it quotes Frederick Douglass: “there is not perhaps anywhere to be found a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than Philadelphia.”

The exhibit then goes on to ask some seemingly edgy questions. Might our revered Constitution have been a pro-slavery document? Does Lincoln deserve his “Great Emancipator” reputation? This latter question is somewhat of a surprise, given how the League engages in Lincoln worship.

A False Dichotomy

But what’s missing is the League’s own origin story. The who, when, and why of its founding.

Instead, the exhibit creates its own mythology. On one side were pro-slavery Southerners and their sympathizers, while in opposition was the Union League, which supported the Union, Lincoln, and the abolition of slavery—working “side by side” as “important allies” with abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Juxtaposed quotations frame this narrative. The abolitionist Douglass faces off against the white supremacist Chief Justice of the United States, Roger Taney; Abraham Lincoln is quoted against Alexander Stephens, the Vice President of the Confederacy. Of course, we don’t have to ask which side the Union League was on.

The problem, however, is that this tidy framing doesn’t reflect the far messier truth about the League in its early days.

Divided City, Divided Social Club

When it was launched in early 1863—the Civil War was already almost half over—the Union League’s stated objective was “to discountenance and rebuke by moral and social influences all disloyalty to the Federal government.”1 Notice that there’s not a word about being a partisan political club, yet alone any disapproval of slavery.

A majority of the early members were probably not even strong supporters of Lincoln. If a contemporaneous League survey is even partially correct,2 significantly more League members were Democrats—the opposition party to Lincoln—than were Republicans. As a League charter member reminisced later, “Lincoln was not a popular President in the early days, not even in active circles of the Union League.”3

Pro-Union, Not Pro-Racial Equality

League members were certainly pro-Union—they had to be, to qualify for membership—and thus they viewed the Southerners in rebellion, and their supporters in the North, as traitors. But being in favor of the Union didn’t equate with being pro-Lincoln or anti-slavery.

Many of these men would have been pleased to see the Civil War end, even if that meant leaving slavery intact.

Philadelphia attorney Daniel Dougherty, a prominent League charter member, held views on Black emancipation that were probably typical of many members. According to another League charter member, Dougherty “had no interest in the negro, and would not have fired a gun for all the negroes that ever came from the Congo lands.”4

The League’s first president, Pennsylvania Attorney General William Morris Meredith, is another example of the range of attitudes on racial equality within the League. The League’s members elected him unanimously at their start-up meeting, expecting, as one official League history put it, that his “judiciously conservative” attitude “would naturally draw many moderate and hesitating men into [the League’s] current.”5

That “judiciously conservative” attitude apparently included a life-long belief that only white men should have the right to vote. Although Meredith’s personal views were anti-slavery, in 1838, as a delegate to the Pennsylvania constitutional convention, he voted for an amendment that stripped free Black men in Pennsylvania of their right to vote.6 Roughly 30 years later, he opposed the post-Civil War amendment to the U.S. Constitution that extended voting rights to Black men.7

This, then, was the League at the outset: white men who came together because they wanted to preserve the Union against the rebellious Southern states. They also wanted membership in a social club that would evidence their privileged position in society. Beyond that, however, it’s impossible to say that they all would have agreed on much of anything—certainly not on issues of Black civil rights. The League itself reflected these differences of view and opinion.

The League’s White-Only Regiments

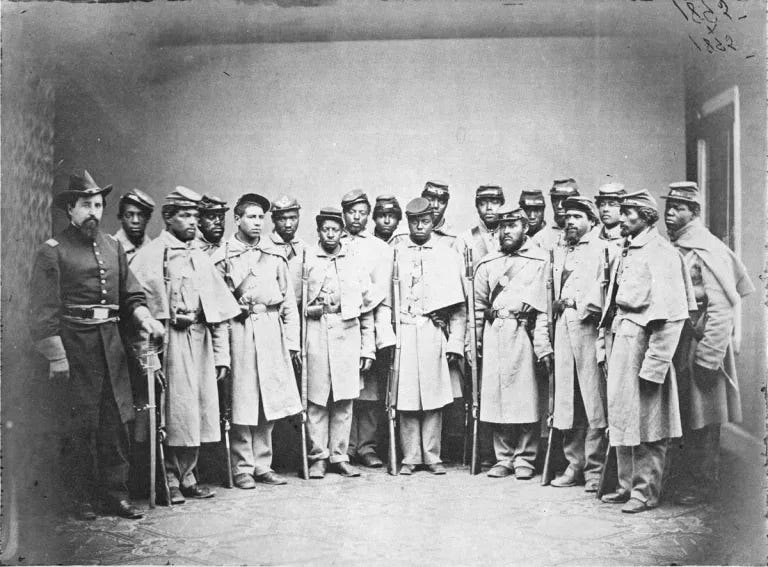

“A City Divided” repeatedly references the League’s support for the Union war effort through military recruiting, including the recruitment of Black troops. The exhibit states that the League “led the recruitment, funding, and establishment of an additional 11,000 United States Colored Troops (USCTs, federal black soldiers).” The League did nothing of the sort.

When presented with the opportunity to recruit and train Black troops, the Union League rejected it.

The enlistment of Black soldiers was among the most controversial of Union war-time issues. Racist whites opposed it, believing that Black men lacked the bravery, loyalty, and resolve necessary for military service. The idea of Black men being armed and trained to fight was unthinkable to those wishing to see them confined only to servile roles. At the same time, everyone seems to have understood that the participation of these men in the war could be (perhaps would be) a direct route to their achieving equality—and that again was something many whites resisted.

In mid-1863, just six months after the League’s founding and just before the Battle of Gettysburg, the League launched its “Committee on Enlistments,” an in-house effort that recruited only white soldiers by offering significant enlistment bonuses.

At roughly the same time, and after some internal League meetings with Frederick Douglass, who was active in the local Black recruitment effort, the League backed away from any similar effort for Black enlistment. As the League’s first official history, written only 20 years after the League’s founding, put it, Black recruitment “involved so much conflict with latent prejudice that the officers of the League were unwilling to commit the organization to its advocacy.”8

To their credit, a “faction of the Union League”9 (as described by a modern historian) formed, along with some non-members, an organization independent of the League and with its own bylaws—the “Supervisory Committee for the Recruitment of Colored Troops.” That faction—presumably they were the ones without that “latent prejudice”—was only a small minority of the entire League membership. The Supervisory Committee ultimately raised and trained 11,000 Black soldiers at Camp William Penn—the Supervisory Committee’s training site in what is now Cheltenham—even though it was initially unable to offer enlistment bonuses.

On the issue of Black recruitment, “A City Divided” gives us an account that is both historically inaccurate and essentially a “white savior” narrative. It omits the fact that the successful effort to raise and train Black troops in Philadelphia depended both on the advocacy of leaders within the Black community and on the initiative of the Black enlistees who responded to that advocacy.

The Vantage Point of Privilege

The Union League’s history is essentially the history of whiteness, yet in the Civil War context the history of Black people is integral and indispensable. This results in an inherent and problematic historical tension in the exhibit’s design and presentation. After all, the League is notorious for not accepting a Black member until more than a century after the end of the Civil War.

Is it really any surprise that Black people seem, at best, to be only on the periphery of the League’s Civil War story?

But on a recent follow-up visit to the exhibit, I was pleased to see a significant new addition on loan from the Lest We Forget Museum of Slavery: a display case, positioned so that it can’t be missed at the entrance, containing a set of wrist shackles “used on enslaved Africans in the transatlantic slave trade.” The accompanying label explains how the agricultural economy in the South was based on an enslaved population of 4 million—32 percent of the entire southern population at the outbreak of the Civil War. This horrifically powerful artifact, which doesn’t directly relate to the League itself—an after-thought on the part of exhibit organizers?—connects with Black history like nothing else in the exhibit.

While “A City Divided: The Civil War, Philadelphia & The Union League” falls far short as an accurate account of the Union League’s Civil War origin story, what it reveals about the League today may be far more telling.

Chronicle of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Union League, 1902), p. 58.

Maxwell Whiteman, Gentlemen in Crisis: The First Century of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Union League, 1975), p. 26.

Chronicle of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Union League, 1902), p. 50 (reprinting John Russell Young reminiscence of Daniel Dougherty from the Evening Star, Sept. 17, 1892).

Chronicle of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Union League, 1902), p. 50 (reprinting John Russell Young reminiscence of Daniel Dougherty from the Evening Star, Sept. 17, 1892).

George Parsons Lathrop, History of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1884), p. 42.

Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, to Propose Amendments to the Constitution, Commenced and Held at Harrisburg, on the Second Day of May, 1837, vol. 9, pp. 352-354, and vol. 10, p. 106 (Harrisburg, PA: Packer, Barrett, and Parke, 1837–38). Meredith’s support for inserting the word “white” as a qualification of suffrage in the Pennsylvania Constitution is also noted in Richard Lewis Ashhurst, “William Morris Meredith 1799-1873,” 55/46 American Law Register (1907), p. 221.

Richard Lewis Ashhurst, “William Morris Meredith 1799-1873,” 55/46 American Law Register (1907), p. 241.

George Parsons Lathrop, History of the Union League of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1884), p. 52.

James M. Paradis, Strike the Blow for Freedom: The 6th United States Colored Infantry in the Civil War (White Mane Books, 1998), p. 7 (citing Whiteman, Gentlemen in Crisis, p. 46).